By Adam Kurtz | Reprinted with permission from UND Today

After successful pressure-suit test at UND, Helios Horizon pilot preps for record-breaking flight in Nevada

Some tense moments arose on Nov. 8 in the room housing UND’s high-altitude chamber, located on the ground floor of Odegard Hall.

But all was well in the end. UND Aerospace physiologists successfully assisted Helios Horizon — a private electrical aviation entity — test a partial-pressure suit, a piece of equipment needed for pilot safety when flying at high altitudes. That meant pilot Miguel Iturmendi had to sit in the subway car-like chamber while UND technicians decreased the air pressure to create the conditions he will experience flying in an unpressurized cockpit at more than 44,000 feet.

A failure of the suit, or other piece of equipment, could have led to physical consequences such as “the bends,” otherwise known as decompression sickness, which many may associate with undersea divers. It also impacts pilots flying at high altitudes.

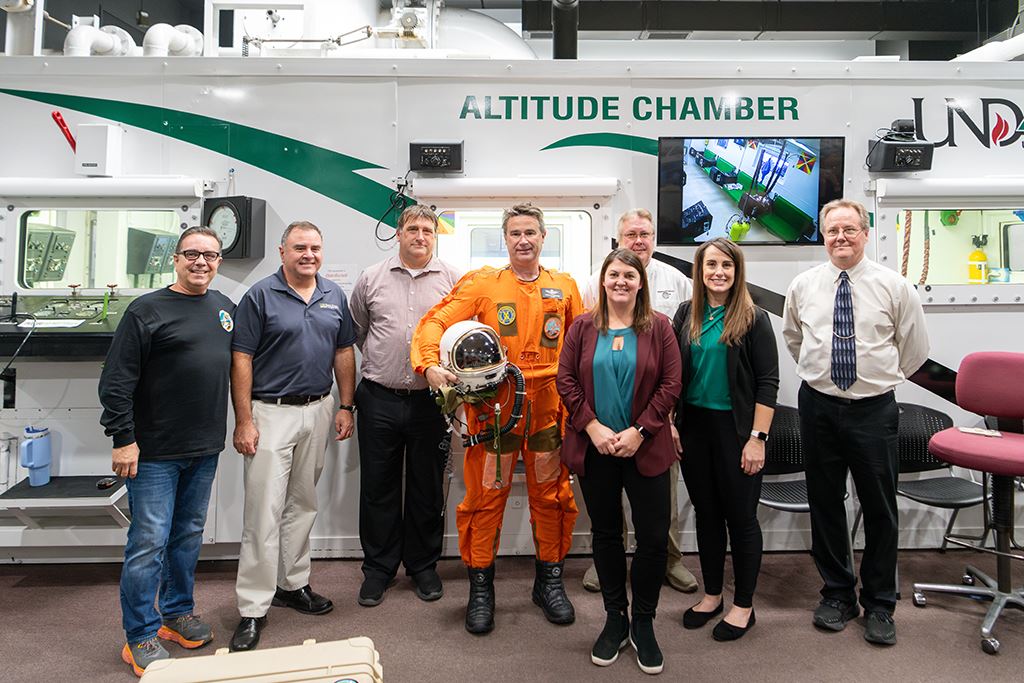

Helios Horizon pilot Miguel Iturmendi stands with his project manager, Javier Merino (far left), UND Space Studies Chair Pablo De León and the UND team members who operate the high-altitude chamber. Photo by Arjun Jagada/School of Aerospace Sciences.

“When you go up to altitude, we lose the atmospheric pressure,” explained Tom Zeidlik, UND’s director of Aerospace Physiology. “That atmospheric pressure is what keeps the nitrogen in our blood. As soon as you lose that pressure, the nitrogen comes out of the solution, so we get air bubbles in our tissue — and that’s how we get the bends.”

Zeidlik, speaking to this reporter (who tries to avoid the deep end of the pool, much less high altitudes, and is not a good flyer) broke down the importance of the pressure suit:

“He has inflatable bladders inside his suit. It’d be like when I pull my shirt real tight. So, instead of using atmospheric pressure, he is using the pressure from the suit to keep all the bubbles inside, so he doesn’t end up with decompression sickness.”

Why do this? Why test the suit at UND?

Iturmendi and project manager Javier Merino are with Helios Horizon, the company that is working to advance electric or battery-powered flight. They are doing that by setting and then smashing records for high-altitude flight in a battery-powered airplane.

Iturmendi holds the current record of about 16,000 feet, set in June 2023. Early next year, he intends to blow past that record by flying at about 45,000 feet in Nevada.

For Merino, it’s about proof of concept; that electrical planes have a place in aviation.

“We’ve seen that electric aviation is the future, so we wanted to prove the concept that we can fly high with batteries, when people thought it was not possible,” he said.

Reaching an altitude of 45,000 feet in the electric plane meant testing the suit. It just so happens that pilot Iturmendi knows Pablo de León, chair of the Department of Space Studies, and his work designing spacesuits. The pair spoke at a conference in Argentina in April, and Iturmendi broached the idea of using UND’s altitude chamber.

De León agreed and ran the idea by Aerospace Dean Robert Kraus, who gave the test the green light.

The test got started at 9 a.m. Nov. 8, with Iturmendi breathing pure oxygen for about 100 minutes, prior to the chamber door being sealed. That purges the blood of nitrogen and is done prior to an event that exposes one to great changes in air pressure, De León said.

A Tense Moment

Once the test got underway, Steven Martin, manager of aerospace physiology operations, sat at the control panel of the chamber and communicated with Iturmendi about altitude, and how he was feeling. Every so often, as the pressure decreased in the chamber, he asked Iturmendi “cognitive questions,” to make sure he was not experiencing any difficulty in thinking that would have indicated a medical problem.

Miguel Iturmendi and Javier Merino, with Helios Horizon, go over equipment, while Pablo de Leon, UND Space Studies professor, assists. Photo by Arjun Jagada/School of Aerospace Sciences.

Miguel Iturmendi and Javier Merino, with Helios Horizon, go over equipment, while Pablo de Leon, UND Space Studies professor, assists. Photo by Arjun Jagada/School of Aerospace Sciences.

“What’s 6 times 6 times 2?” went one question. “72,” Iturmendi answered, without difficulty.

Had there been a medical emergency, Eric Toutenhoofd, an aerospace physiology technician and instructor, was also inside the chamber — in a sealed and separate compartment — to render assistance. Toutenhoofd experienced only 25,000 feet of atmospheric pressure, which is the altitude UND Aerospace students experience during their training.

The idea was to have a trained person in the chamber who’d be more readily able to have access to Iturmendi. Outside the chamber were two Altru paramedics and an off-duty member of the Grand Forks Fire Department. As luck would have it, they were not needed, though there was a tense moment.

As the air pressure decreased — simulating an increase in altitude — Iturmendi seemed to have some difficulty closing the visor of his helmet. His fingers also seemed to tremble, and the room outside the chamber quickly got very quiet.

“He got our attention,” Zeidlik said, but a quick cognitive question later determined he was not in any danger.

Martin announced they hit 44,000 feet, and Iturmendi quickly gave the signal to level off and descend.

And just like that, the test was over. Altitude Chamber Technicians Alyssa Geatz and Jennifer Watne slowly restored the air pressure in the two compartments to normal (for them, the work was a balancing act of maintaining airflow in and out of the chamber).

“I’m alive!” Iturmendi shouted to applause, as he finally exited the chamber. He breathed deeply, to get used to the normal air pressure. He described the experience as uncomfortable to say the least, but the test was successful.

He said he is looking forward to the record-breaking high-altitude flight, and to flights even beyond that:

“Next year, we will try to do a stratospheric flight,” he said, and mentioned the possibility of coming back to UND for more testing on the pressure suit.

Speaking after the test, Dean Robert Kraus said he was pleased with the results, and with the efforts of the UND and Helios Horizon teams.

“UND Aerospace has long been recognized as one of the top aviation programs in the country,” he said. “Our faculty and researchers continue to expand the limits, and Tom Zeidlik and his team of experts in aerospace physiology are recognized across the industry. The group from Helios Horizon has been great to work with, and we look forward to their success in setting new altitude records for electric aircraft.”

Steven Martin, manager of aerospace physiology operations (right) and Altitude Chamber Technician Alyssa Geatz look on while Miguel Iturmendi tests his suit. Photo by Arjun Jagada/School of Aerospace Sciences.